31/12/21 - 22/02/22

Daniel Stempfer

Bowl Cuts

Salutations, Ye Salt of the Earth!

宋子曰:天有五氣,是生五味。潤下作咸,王訪箕子而首聞其義焉。口之于味也,辛、酸、甘、苦,經年絕一無恙。獨食鹽,禁戒旬日,則縛雞勝匹,倦怠懨然。豈非天一生水,而此味為生人生氣之源哉?四海之中,五服而外,為蔬為穀,皆有寂滅之鄉,而斥鹵則巧生以待。敦知其以然?

-- 宋應星, 《天工開物》

The Master Song said: The essence of Nature’s five elements begot the five tastes, and the fact that salinity could be produced from moisture was known only after King Wu of Zhou asked the Grand Tutor Jizi. A man can survive without hot, sour, sweet, or bitter, but ten days without salt will drain him of all energy. Is it not so, then, just as from the One of Nature sprung forth Water, that Salt coming from Water became the Origin of humanity’s essence? Across the four seas, there must be many barren wastelands, and yet it is precisely there that Salt is begotten and awaits us—and such, who would have known!

-- Song Yingxing (1637 AD) Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature)

Who would have known—the myriad twists and turns of the past year and the many more to come that await us? And so the tides of history gather us here and now on Elliot’s barren rocks; but where is the autochthonous salt that awaits us—whence is our salt of the earth? In these unknowable times, it becomes all the more necessary to reflect on our essence, to stop and ponder where we stand, trapped or free: How do we situate ourselves within a greater cosmos of Nature—of minerals, viruses, and other species, of Society, of History, or perhaps within an individual construction of Self reduced to biochemical excretions of Salt? If, as Song Yingxing observed, salt harvested from Nature’s moisture—via techniques of mining salt fields and a vast history of salt trading—became the essential external source for human civilization, to what extent may we reverse the equation: that human individuals ourselves contain the innate capacity to become the self-sufficient production of moisture that begets salt?

This exhibition is, in essence, a product of Time—condensed into 9 grams of salt and three works, each of which the artist considers a form of “recording”. In this sense, the works are simultaneously a record of a single year as well as of a particular lived contemporary moment in which the artist and much of human society has been asked to come to terms with isolation and rethink the way we have come to live as individuals in the world. For some it meant dusting off old volumes at home, for others, like the artist, it meant finding solace in the only outdoor activity permissible at the height of the lockdown: running. As an evolutionary trait, this survival adaptation has allowed the human species to run away from and run after things. As an exercise, the repetitious labor of running has the added benefit of maintaining physical health and sanity, but, all the same, results in a byproduct of salts in within pores of the skin, allowing for the perspiration of human sweat. Can our salt be a measure of time? Can a history of human civilization, dripped materially before our eyes, be condensed within the sweat production of a single man, distilled into nine grams of coeval human salinity?

Through the process of the artist’s own physical ‘creation’ of salt from sweat, baking into bread, and transformation into digital objects which are materially remade, Daniel Stempfer’s Bowl Cuts takes on such a reflexive question of self-sufficiency, beginning with his own labor and art practice and resulting in a project that precipitates into a production of three sculptures within which materiality and concept intermingle across manifold spatiotemporal layers.

When the artist described to me his project, a year in the making, it led me onto a dual investigation of biochemical salt concentrations in sweat and the human history of salt and sweat—that is the human labor that comes with our social existence in the world. On one hand, a long history of the salt production and trade serves as the background and conceptual link between the historicity of the soil upon which the artist currently stands and his roots in Salzburg, two important historical sites of salt production and trade in history. On the other, the artwork challenges us to look within and reflect on the contemporary choices between the health of society and the autonomy of the individual, the relations of self-sufficiency versus global connectivity, and ultimately the questions of history and humanity. Salubrity, salvation, salinity thus find their roots in a deep-seated entanglement between the essence of our humanity and the salt of our earth. At the same time, now is the present in which we ourselves become the makers of the contemporary, the perspirers of possibility. Within the works, Time itself is transformed into material form—vessels of man’s sweaty labor.

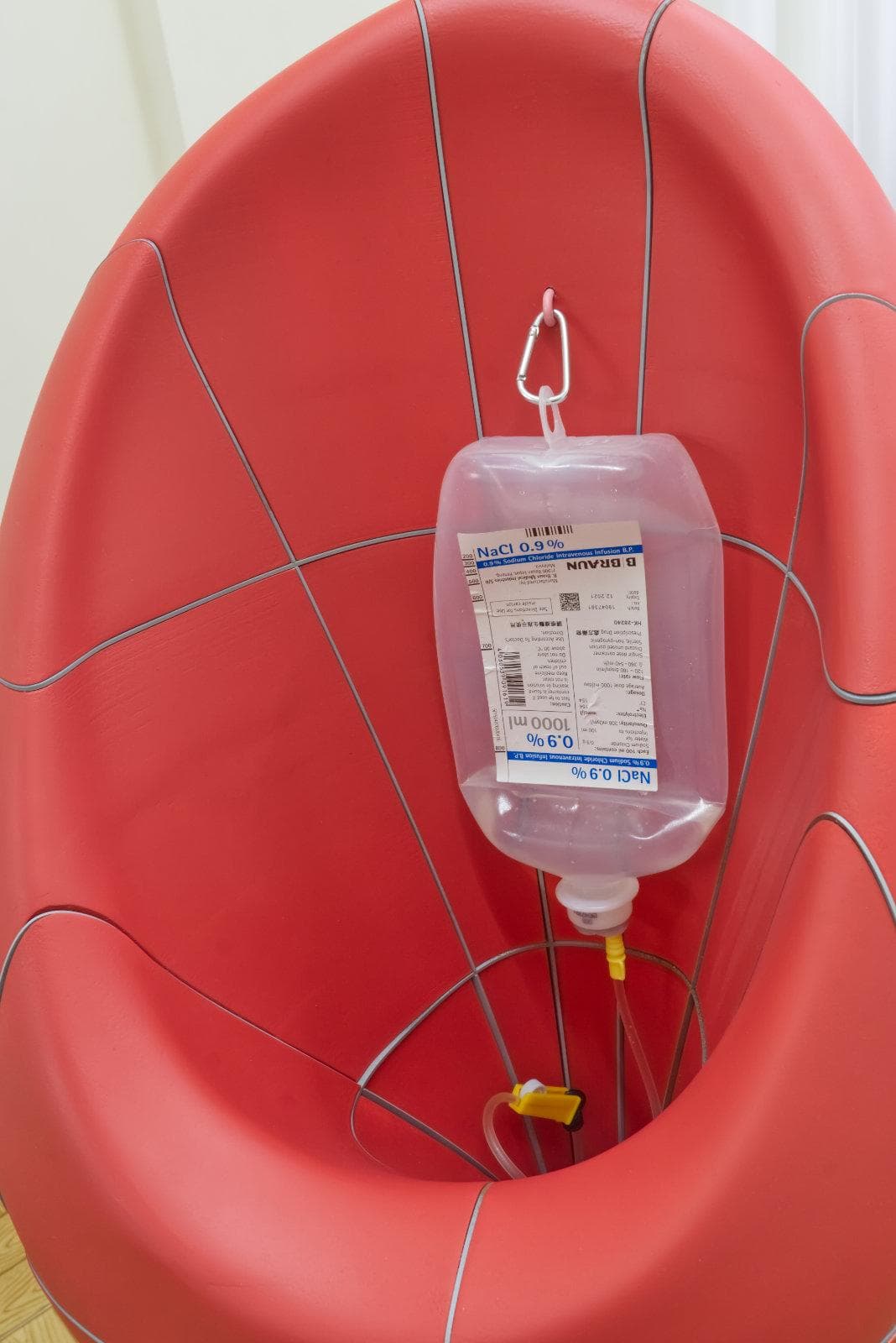

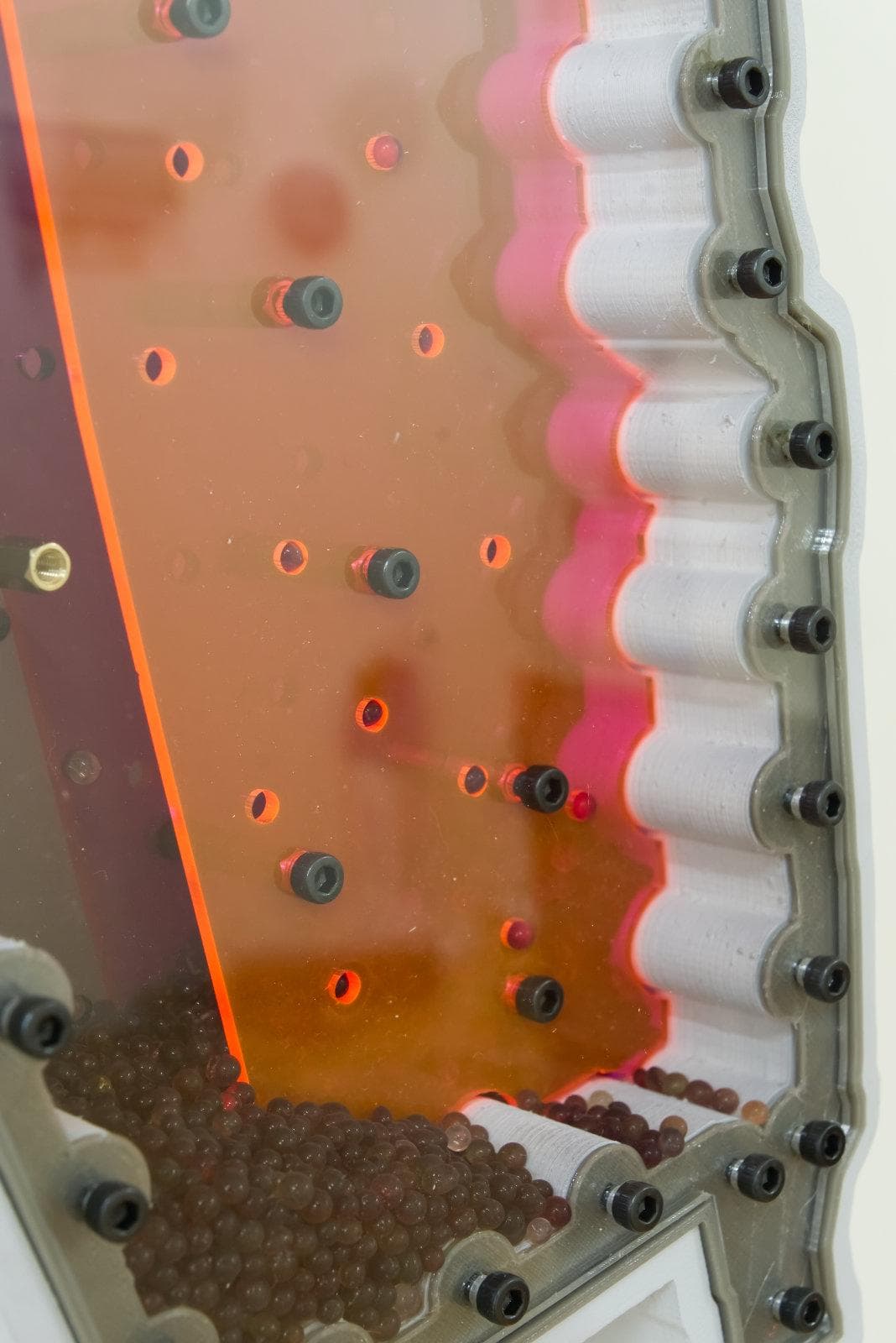

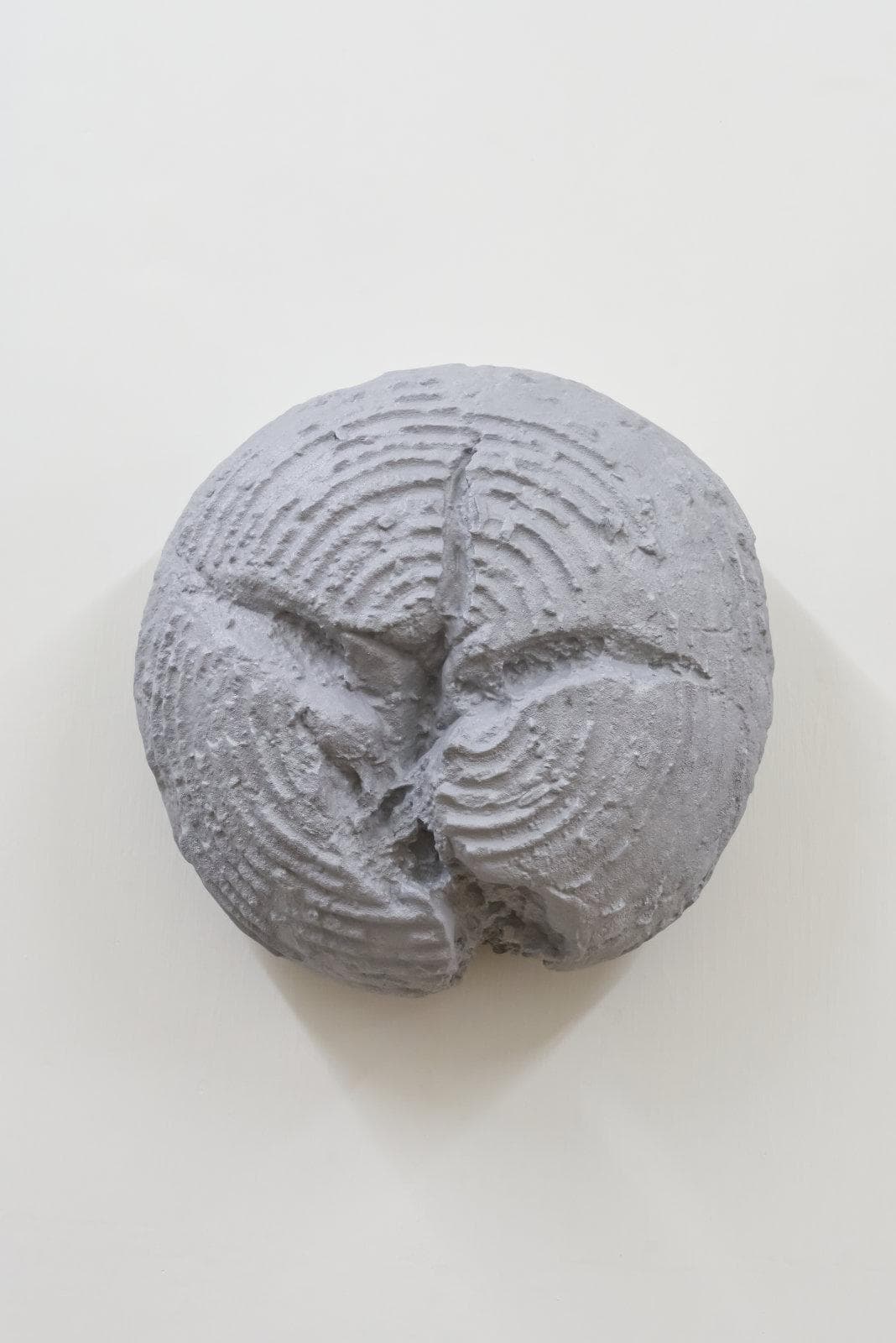

As a saline solution drips, like beads of sweat, from within an hourglass-shaped sculpture, we are challenged to face the double labor of passing time and the production of salt crystallizing before our eyes. Mounted on the walls, loaves of brass and aluminum bread are twice baked—once from the flour mixed with the salt of his sweat and baked a second time from the digital scan of that bread—the product of a cross-border traffic of objects at a time when humans could not make the same journey. Does the derivative product of the labor of man-made salt in doubly baked bread (the giving of salt and bread being a traditional show of Greek hospitality) allow us to transgress contemporary restrictions of in-person exchange? Or might our cultural values be transformed through a reflection of the human condition, for example, in Stempfer’s response to Benvenuto Cellini’s Saliera (or “salt cellar”) which reappropriates a gilded cosmological throne of a precious global commodity of the 16th century back to a 21st century digitally printed reproduction of GPS data from the spatialized “runs” of a single man’s physical sweat?

In the end, is self-sufficiency not that which we have already been outfitted from the very beginning—our being the very own salt production that we have forgotten? Despite, or perhaps as a result of, the peculiarities that shape our contemporary human condition, the viewer is reminded that beyond the global human history of salt trading, we too are autochthonous producers of salt, through individual human labor.

Finally, it is fitting that the inaugural show at Feyerabend should, in the fashion of its namesake philosopher Paul Feyerabend, simultaneously question our histories of epistemological understanding and bring together a finality of an arduously year-long anthropological reflection on self-sufficiency, society, and self. We are all ready, in essence, to “call it a day” (Feierabend machen) and ring in a new space to dive into the unending questions of art, of our contemporary, and of our shared humanity — Jetzt, machen wir Feyerabend!

Chris K. Chan

Hong Kong, 31 December 2021

Exhibition kindly supported by:

宋子曰:天有五氣,是生五味。潤下作咸,王訪箕子而首聞其義焉。口之于味也,辛、酸、甘、苦,經年絕一無恙。獨食鹽,禁戒旬日,則縛雞勝匹,倦怠懨然。豈非天一生水,而此味為生人生氣之源哉?四海之中,五服而外,為蔬為穀,皆有寂滅之鄉,而斥鹵則巧生以待。敦知其以然?

-- 宋應星, 《天工開物》

The Master Song said: The essence of Nature’s five elements begot the five tastes, and the fact that salinity could be produced from moisture was known only after King Wu of Zhou asked the Grand Tutor Jizi. A man can survive without hot, sour, sweet, or bitter, but ten days without salt will drain him of all energy. Is it not so, then, just as from the One of Nature sprung forth Water, that Salt coming from Water became the Origin of humanity’s essence? Across the four seas, there must be many barren wastelands, and yet it is precisely there that Salt is begotten and awaits us—and such, who would have known!

-- Song Yingxing (1637 AD) Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature)

Who would have known—the myriad twists and turns of the past year and the many more to come that await us? And so the tides of history gather us here and now on Elliot’s barren rocks; but where is the autochthonous salt that awaits us—whence is our salt of the earth? In these unknowable times, it becomes all the more necessary to reflect on our essence, to stop and ponder where we stand, trapped or free: How do we situate ourselves within a greater cosmos of Nature—of minerals, viruses, and other species, of Society, of History, or perhaps within an individual construction of Self reduced to biochemical excretions of Salt? If, as Song Yingxing observed, salt harvested from Nature’s moisture—via techniques of mining salt fields and a vast history of salt trading—became the essential external source for human civilization, to what extent may we reverse the equation: that human individuals ourselves contain the innate capacity to become the self-sufficient production of moisture that begets salt?

This exhibition is, in essence, a product of Time—condensed into 9 grams of salt and three works, each of which the artist considers a form of “recording”. In this sense, the works are simultaneously a record of a single year as well as of a particular lived contemporary moment in which the artist and much of human society has been asked to come to terms with isolation and rethink the way we have come to live as individuals in the world. For some it meant dusting off old volumes at home, for others, like the artist, it meant finding solace in the only outdoor activity permissible at the height of the lockdown: running. As an evolutionary trait, this survival adaptation has allowed the human species to run away from and run after things. As an exercise, the repetitious labor of running has the added benefit of maintaining physical health and sanity, but, all the same, results in a byproduct of salts in within pores of the skin, allowing for the perspiration of human sweat. Can our salt be a measure of time? Can a history of human civilization, dripped materially before our eyes, be condensed within the sweat production of a single man, distilled into nine grams of coeval human salinity?

Through the process of the artist’s own physical ‘creation’ of salt from sweat, baking into bread, and transformation into digital objects which are materially remade, Daniel Stempfer’s Bowl Cuts takes on such a reflexive question of self-sufficiency, beginning with his own labor and art practice and resulting in a project that precipitates into a production of three sculptures within which materiality and concept intermingle across manifold spatiotemporal layers.

When the artist described to me his project, a year in the making, it led me onto a dual investigation of biochemical salt concentrations in sweat and the human history of salt and sweat—that is the human labor that comes with our social existence in the world. On one hand, a long history of the salt production and trade serves as the background and conceptual link between the historicity of the soil upon which the artist currently stands and his roots in Salzburg, two important historical sites of salt production and trade in history. On the other, the artwork challenges us to look within and reflect on the contemporary choices between the health of society and the autonomy of the individual, the relations of self-sufficiency versus global connectivity, and ultimately the questions of history and humanity. Salubrity, salvation, salinity thus find their roots in a deep-seated entanglement between the essence of our humanity and the salt of our earth. At the same time, now is the present in which we ourselves become the makers of the contemporary, the perspirers of possibility. Within the works, Time itself is transformed into material form—vessels of man’s sweaty labor.

As a saline solution drips, like beads of sweat, from within an hourglass-shaped sculpture, we are challenged to face the double labor of passing time and the production of salt crystallizing before our eyes. Mounted on the walls, loaves of brass and aluminum bread are twice baked—once from the flour mixed with the salt of his sweat and baked a second time from the digital scan of that bread—the product of a cross-border traffic of objects at a time when humans could not make the same journey. Does the derivative product of the labor of man-made salt in doubly baked bread (the giving of salt and bread being a traditional show of Greek hospitality) allow us to transgress contemporary restrictions of in-person exchange? Or might our cultural values be transformed through a reflection of the human condition, for example, in Stempfer’s response to Benvenuto Cellini’s Saliera (or “salt cellar”) which reappropriates a gilded cosmological throne of a precious global commodity of the 16th century back to a 21st century digitally printed reproduction of GPS data from the spatialized “runs” of a single man’s physical sweat?

In the end, is self-sufficiency not that which we have already been outfitted from the very beginning—our being the very own salt production that we have forgotten? Despite, or perhaps as a result of, the peculiarities that shape our contemporary human condition, the viewer is reminded that beyond the global human history of salt trading, we too are autochthonous producers of salt, through individual human labor.

Finally, it is fitting that the inaugural show at Feyerabend should, in the fashion of its namesake philosopher Paul Feyerabend, simultaneously question our histories of epistemological understanding and bring together a finality of an arduously year-long anthropological reflection on self-sufficiency, society, and self. We are all ready, in essence, to “call it a day” (Feierabend machen) and ring in a new space to dive into the unending questions of art, of our contemporary, and of our shared humanity — Jetzt, machen wir Feyerabend!

Chris K. Chan

Hong Kong, 31 December 2021

Exhibition kindly supported by: